O comportamento sexual humano é determinado por motivações complexas, mesmo quando não parece. Talvez isto represente uma das principais diferenças que os humanos têm em relação às demais espécies do reino animal. As observações de Sigmund Freud e seus construtos teóricos contribuíram significativamente para identificar algumas das peculiaridades mais importantes da sexualidade humana. O romance “NO JARDIM DO OGRO” da franco-marroquina LEÏLA SLIMANI (nascida em Rabat, Marrocos, 1981) mergulha neste universo.

Ogro é o nome dado a um monstruoso ser mitológico que se alimenta de carne humana. O enredo aborda um período da vida da jornalista Adele, casada com Richard e mãe do garoto Lucien, em que ela se lança freneticamente numa sequência de atos sexuais (talvez coubesse melhor a expressão “atos carnais”) com muitos homens. É algo compulsivo, do que ela faz segredo (exceto para uma amiga) e que ameaça a já precária estabilidade em sua vida afetiva e profissional.

Em nenhum momento aparecem menções ao prazer que Adele poderia sentir em seus encontros com os homens. Há somente a necessidade desenfreada antes do ato e a aflição do depois. O desconforto não equivale a culpa por trair o marido ou a receios devido à temerária exposição. É um impulso incontornável, que a arrebata, mas desvinculado de sensualidade. Ela percorre diversos ambientes em busca de encontros, oferecendo sua carne para ser devorada. Não há reciprocidade neste devoramento ou, pelo menos, quanto ao que cada parceiro consome. Não há propriamente desejo denominável sexual anterior aos atos, não há referência a satisfação durante eles e nem restam memórias gozosas. Não há fantasia. É como se ela penetrasse o habitat do ogro, que poderia ser a síntese de todos os homens com quem ela põe em prática a voragem e oferece sua carne. Adele reduz seu corpo a carne e o quer consumido cru. A crueza é um ponto chave. Pouco importa a tipificação do homem consumidor. É só uma questão de circunstâncias.

Lembrando a teoria pulsional freudiana, ou ao menos uma parte dela, é como se a busca incessante que faz a protagonista não correspondesse à realização de desejo sexual, ao enredamento a um objeto que encarnasse a promessa de satisfação ou mesmo que promovesse algum tipo de conquista e posse. Parece não haver antecipação de nenhum tipo de gozo enquanto prazer. O que a move não é algo do que se possa desfrutar. É só descarga de energia a ser dejetada. Talvez uma força inominável dirigida a qualquer indivíduo sem algum atributo apetecível, ele não é o alvo. Não importa o outro, exceto como dispositivo expurgatório. Há aqui uma proximidade com o que Freud indicou ser a pulsão por excelência que em sua nadificação quanto ao objeto impeliria para a extinção, a morte. Trata-se da pulsão de morte nesta perspectiva de compreensão. Para Adele restam só desolamento e a percepção de que a ânsia que a arrasta para o jardim do ogro logo pulsará novamente. É possível que ela se resuma-se predominantemente a isto, ainda que algum desejo de escapar e o amor, débil amor, caibam em seu ser.

Os outros personagens têm importância e devem ser notados, o marido, sua mãe, pai e a amiga que sabe de suas “aventuras”, mas ainda que tenham um mínimo de autonomia ficcional e possam ser implicados na identidade dela, existem a duas galáxias de distância.

O romance é muito interessante também pela verdade que a autora consegue imprimir à tensa narrativa.

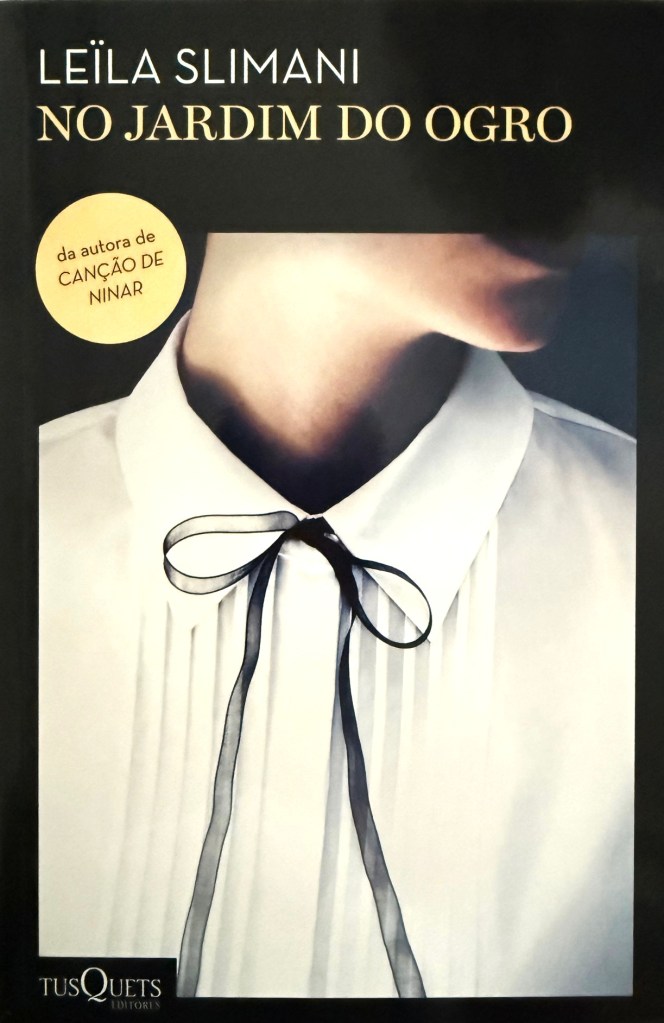

Título da Obra: NO JARDIM DO OGRO

Autora: LEÏLA SLIMANI

Tradutora: GISELA BERGONZONI

Editora: EDITORA PLANETA (TusQuets)

Human sexual behavior is shaped by complex motivations, even when it does not appear so. Perhaps this constitutes one of the principal differences between human beings and the other species of the animal kingdom. The observations of Sigmund Freud and his theoretical constructs contributed significantly to identifying some of the most important peculiarities of human sexuality. The novel In the Ogre’s Garden by the Franco-Moroccan writer Leïla Slimani (born in Rabat, Morocco, 1981) plunges into this universe.

An ogre is the name given to a monstrous mythological being that feeds on human flesh. The plot addresses a period in the life of the journalist Adèle, married to Richard and mother of the boy Lucien, during which she throws herself frenetically into a succession of sexual acts (perhaps the expression “acts of the flesh” would be more fitting) with numerous men. It is something compulsive, which she keeps secret (save from a friend), and which threatens the already fragile stability of her emotional and professional life.

At no point is there any mention of the pleasure Adèle might experience in her encounters with these men. There is only the unbridled necessity preceding the act and the anguish that follows. The discomfort is not equivalent to guilt over betraying her husband, nor to fears arising from reckless exposure. It is an inescapable impulse that seizes her, yet one detached from sensuality. She moves through various environments in search of encounters, offering her flesh to be devoured. There is no reciprocity in this devouring—or at least not in terms of what each partner consumes. There is no properly nameable prior sexual desire, no reference to satisfaction during the acts, nor any lingering pleasurable memory. There is no fantasy. It is as though she were entering the ogre’s habitat, which might stand as the synthesis of all the men with whom she enacts this voracity and offers her flesh. Adèle reduces her body to meat and wishes it consumed raw. Rawness is a key point. The typology of the consuming man matters little. It is merely a matter of circumstance.

Recalling Freudian drive theory, or at least part of it, it is as though the protagonist’s incessant quest does not correspond to the fulfillment of sexual desire, nor to an entanglement with an object embodying the promise of satisfaction or even promoting some form of conquest and possession. There appears to be no anticipation of pleasure as enjoyment. What moves her is not something to be savored. It is simply a discharge of energy to be expelled. Perhaps an unnamed force directed toward any individual devoid of appealing attributes; he is not the aim. The other does not matter, except as an expurgatory device. Here there is proximity to what Freud indicated as the drive par excellence, which, in its objectless negation, would impel toward extinction—toward death. It is the death drive in this interpretive perspective. For Adèle there remain only desolation and the awareness that the craving that drags her into the ogre’s garden will soon pulse again. It is possible that she is predominantly reducible to this, though some desire to escape—and love, a frail love—may still inhabit her being.

The other characters have importance and deserve notice—the husband, her mother and father, and the friend who knows of her “adventures”—yet even if they possess a minimum of fictional autonomy and may be implicated in her identity, they exist at a distance of two galaxies.

The novel is also compelling for the truth the author succeeds in imprinting upon this tense narrative.

Title: In the Ogre’s Garden

Author: Leïla Slimani

Translator: Gisela Bergonzoni

Publisher: Editora Planeta (TusQuets)