São sempre incertas as interpretações dos comportamentos, desde a singularidade das pessoas até o que se dá em coletividades. O que parece paradoxal costuma surpreender, mas a complexidade humana admite contradições. De todo o modo, é possível produzir discursos interessantes ao descrever gente. O conto “BARRO” de James Joyce (Dublin, 1882 – Zurique, 1941), parte de “DUBLINENSES” traz um retrato tocante da personagem Maria durante algumas horas de uma véspera do Dia de Todos os Santos, também chamado de “All-Hallows Eve” em países de cultura anglo-saxônica, mais recentemente o “Halloween”. Feriado amplamente comemorado na Irlanda.

A protagonista é descrita com a aparência que lembra uma bruxa. Muito pequena, tem o nariz enorme, que quase toca o queixo protuberante quando ri. É também uma pessoa doce, conciliadora, cordata. Gasta o pouco dinheiro de que dispõe com presentes para amigos. Ocupa-se deles e deseja-lhes o bem. Sensibiliza-se com pequenas ocorrências que revelam aspectos nobres de desconhecidos. É amada por homens de quem foi babá como se fosse sua verdadeira mãe. Parece sorver os prazeres que lhe são possíveis com alegria. É amável com todos e aprecia a gentileza de outras pessoas. Quando as mulheres solteiras manifestam o desejo de encontrar casamento ela dá mostras de degustar sua independência sem ser uma solitária, pois é capaz de dar e receber amor.

No dito feriado as pessoas divertem-se, comem doces. Entre as brincadeiras tradicionais há a escolha (de olhos vendados) de um pires entre quatro, cada um contendo água, um missal, um anel ou barro, que significam nada, o convento como destino, o casamento ou a morte. Quando Maria entra num desses jogos escolhe o barro e rapidamente uma das pessoas presentes faz com que o troque pelo missal. Evidencia-se o carinho que lhe devotam.

Maria representa muito. Joyce trata daquilo que é menos percebido entre pessoas que enfrentam muitas adversidades, a possibilidade de estar-se bem em condições nas quais a maioria só enxerga agruras. Pode-se pensar na bela generosidade das bruxas, seu espírito talvez superior, quando parecem amaldiçoadas. É relevante o bom olhar de Maria, sua capacidade afetiva. A dureza do destino não pode excluir o que nele há de benfazejo. Ela também traz à cena, numa vertente mais política, o desejo de autonomia que os irlandeses, desvinculando-se do poder inglês e vivendo o que lhes é próprio. Todavia, isto não a priva do bem-viver entre os seus. Há nela um tipo de delicadeza, esteio essencial que a protege, fortalece e ajuda a estabelecer vínculos preciosos com os que a cercam.

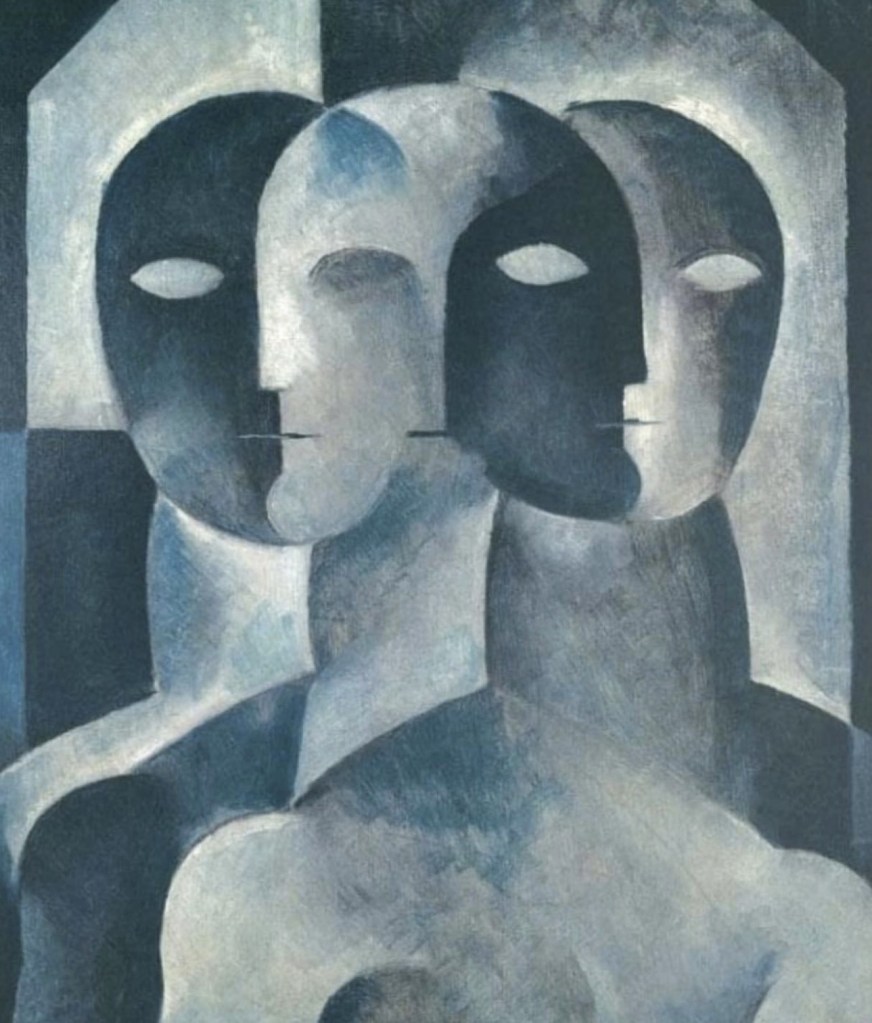

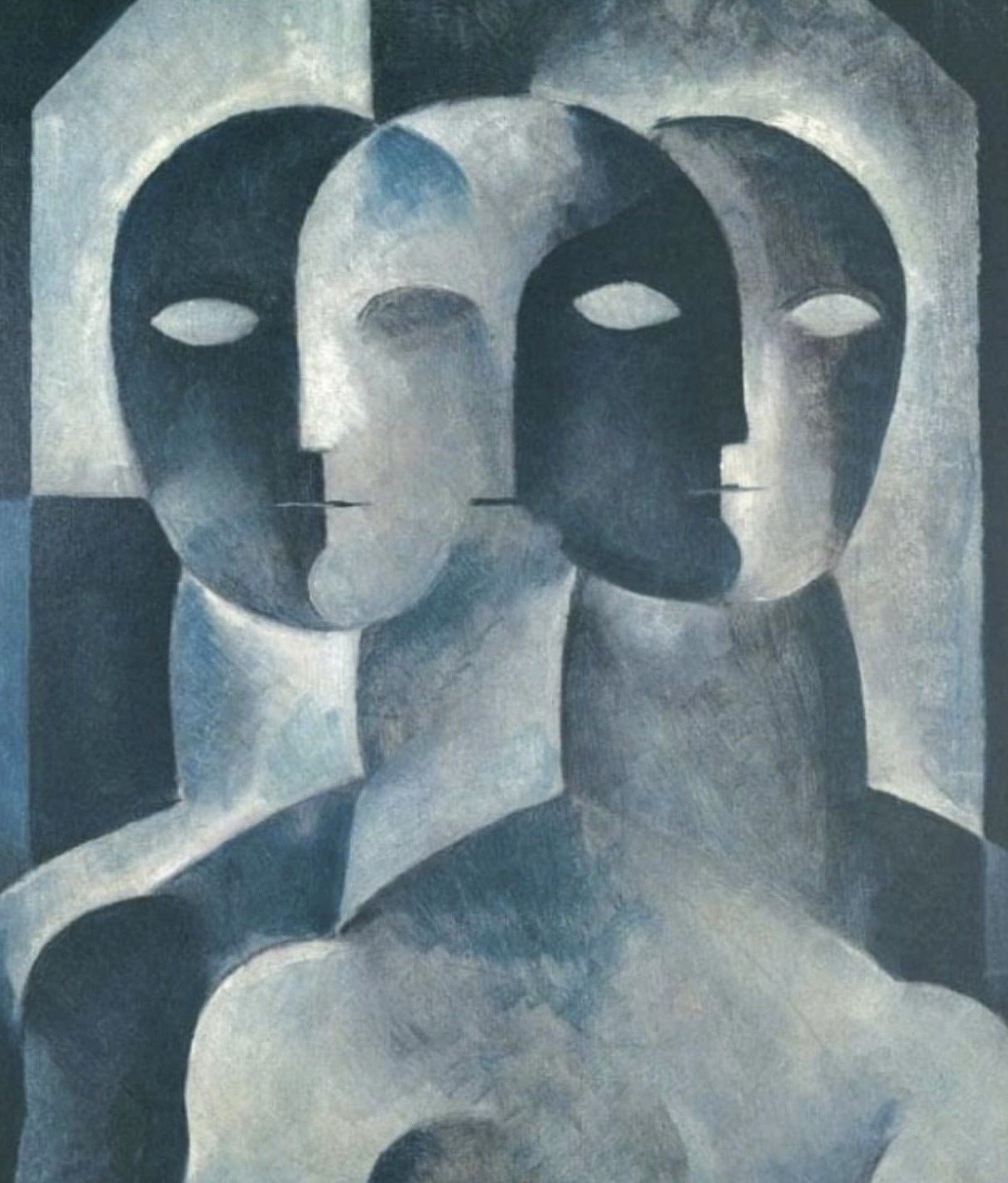

Na ilustração: foto de obra de Ismael Nery (Belém do Pará, 1900 – Rio de Janeiro, 1934)

Título da Obra: BARRO

Autor: JAMES JOYCE

Tradutor: CAETANO W. GALINDO

Editora: PENGUIN/COMPANHIA DAS LETRAS

Clay

Interpretations of human behavior are always uncertain—whether one examines the singularity of individuals or the dynamics of collectives. What seems paradoxical often surprises us, yet human complexity inherently allows for contradiction. Still, it is possible to craft compelling narratives by simply describing people. Clay, one of the stories in Dubliners by James Joyce (Dublin, 1882 – Zurich, 1941), offers a tender portrait of the character Maria over the course of a few hours on the eve of All Saints’ Day—also known in the Anglo-Saxon world as All Hallows’ Eve, or more recently, Halloween. A holiday widely celebrated in Ireland.

The protagonist is depicted with an appearance reminiscent of a witch: she is very small, with a large nose that nearly touches her prominent chin when she laughs. Yet she is also sweet, conciliatory, and mild-mannered. She spends the little money she has on small gifts for her friends, caring deeply for them and wishing them well. She is easily moved by small gestures of kindness from strangers. The men she once nursed as a governess now love her as though she were their real mother. She seems to savor the simple pleasures available to her with genuine joy. She is kind to everyone and delights in the courtesy of others. When the unmarried women around her express their longing for marriage, Maria seems to relish her independence—not as a lonely woman, but as one capable of both giving and receiving affection.

On this holiday, people make merry and eat sweets. Among the traditional games is one in which a blindfolded participant chooses from four saucers—each containing water, a prayer book, a ring, or clay—symbolizing, respectively, nothing, entry into a convent, marriage, or death. When Maria takes her turn, she selects the clay. Immediately, someone in the group discreetly swaps it for the prayer book, revealing the tenderness and affection they feel for her.

Maria stands for much more than herself. Joyce explores what often goes unnoticed among those who face hardship: the possibility of contentment under circumstances most would see only as grim. One might even imagine in her a kind of witch’s generosity—a superior spirit cloaked in misfortune. What matters most is Maria’s benevolent gaze, her emotional openness. Harsh fate cannot extinguish the goodness embedded within it. On a subtler, more political level, Maria also embodies Ireland’s longing for autonomy—for living according to its own nature, free from English dominion. Yet this yearning does not estrange her from her people; rather, she remains rooted among them, a source of quiet strength and grace. In her dwells a gentleness that sustains her, fortifies her, and enables her to form precious bonds with those around her.

Illustration: Photograph of a work by Ismael Nery (Belém do Pará, 1900 – Rio de Janeiro, 1934)

Title: Clay

Author: James Joyce

Translator: Caetano W. Galindo

Publisher: Penguin / Companhia das Letras